Go to The Pavement of the Abbey Church of Desiderius (1066-1071) Go to The History Go to The Technique v

The Pavement of the Abbey Church of Desiderius (1066-1071)

At the behest of Abbot Desiderius (1058-1087), a geometric mosaic floor of polychrome marble was laid for the new abbey church by 1071. Desiderius expressly called on craftsmen from Constantinople who were specialized in the mosaic technique and bought the necessary marbles from Rome.

It is possible to reconstruct the original appearance of the medieval floor thans to the print published by Erasmus Gattola in 1733 to illustrate his history of the abbey (Histoia Abbatiae Cassinensis).

Don Angelo Pantoni noticed and recorded the surviving fragment of the medieval pavement found beneath the pavement from 1728 after the 1944 bombings; he also recovered its most significant fragments, which are on display here at the museum.

In his Chronicle, Leo Marsicanus, a monk at Montecassino at the time of Abbot Desiderius (1058-1087), compares the polychrome marble pavement of the abbey church to a blossoming meadow. Leo also tells about how the abbot obtained ancient marbles in Rome and called expert artists from Byzantium (Istanbul, modern day Turkey) to revive mosaic and marble inlay (opus sectile) techniques.

The floor was refashioned in the 13th century and once more after the 1349 earthquake destroyed the building. In 1728 it was covered with a new, Baroque pavement. This explains why the pavement was badly damaged, but not completely destroyed by the 1944 bombings.

The original appearance of the medieval pavement can be reconstructed thanks to evidence from many sources and documents. Among these there is an important print by Erasmus Gattola published in 1733 as part of his history of the abbey (Historia Abbatiae Cassinensis).

The pavement of Desiderius’ abbey church displayed an interwoven composition delineated by white marble strips forming 66 squares with marble inlay (opus sectile). Its execution was a milestone in the history of mosaic pavements in Italy. In fact, it influenced Roman marble masons working from the 12th to 15th centuries in central and southern Italy.

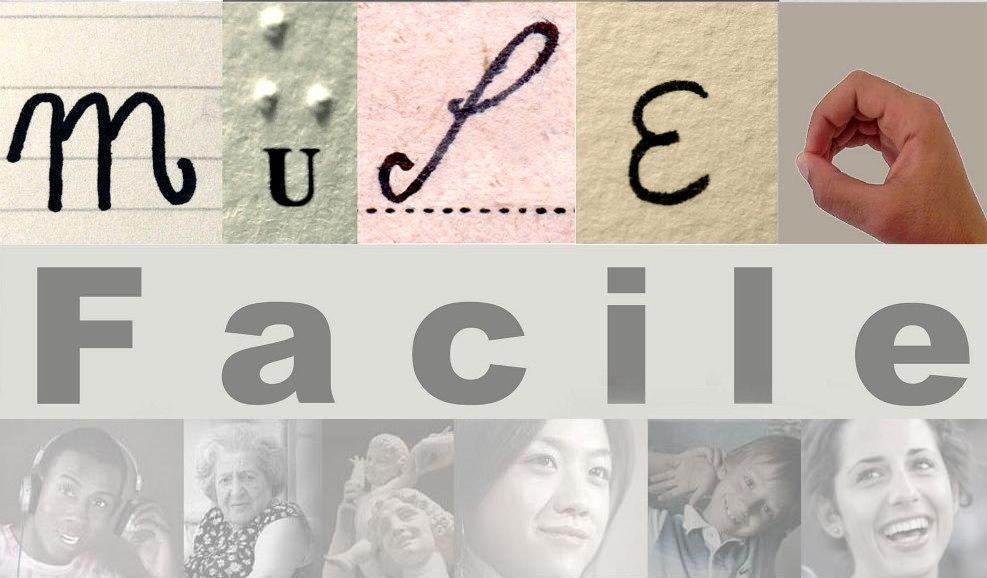

The pavement of the abbey church of Desiderius has been realized with the opus sectile technique, a Latin term meaning “cut work”, a type of polychrome marble mosaic or inlay.

Polychrome marble pavements were already in use in imperial times for formal rooms and large public spaces. While mosaics employ small stone or glass tesserae, this type of pavement employs different kinds of marble slabs, cut and combined in various shapes.

The highly valued marbles came from different parts of the Mediterranean. Making these pavements required carefully systematized work and extraordinary precision in cutting the marble slabs. The decorative motifs were mainly geometric and floral.

Between the 4th and 5th centuries polychrome marble pavements spread across churches in the eastern Mediterranean and the Eastern Roman Empire, also known as the Byzantine Empire (in reference to Byzantium, the ancient name of Constantinople—the empire’s capital—today’s Istanbul).

Throughout the Middle Ages most pavements consisted of simple geometric patterns made of smaller tesserae compared to their Classical counterparts. In Italy, inlaid floors are concentrated around Rome and Lazio, while the Adriatic region has more mosaic floors. In some cases, the two techniques are employed together.

Montecassino’s decorative campaign (1066-1071) played a decisive role of the inlay technique’s revival in the Romanesque period (11th-13th centuries), thanks to the skills of experienced Byzantine artists called by abbot Desiderius, the project’s patron.

Abbot Desiderius, the patron of the new abbey church (1066-1071), procured marble, columns and capitals from Rome transporting them by sea to the mouth of the Garigliano, then on to Suio and finally to Montecassino. In the Middle Ages, marbles were often taken from Classical buildings and reused to refurbish other sites. The Roman Forum became the largest quarry for such marble.

It is impossible to determine precisely which marbles were employed in the medieval pavement of Montecassino. In the fragments that have come down to us—on display here—you can admire some of Ancient Rome’s most precious marbles: imperial red porphyry from Egypt, antique green porphyry (serpentine) from Laconia, a limestone called ‘palombino’, white luna marble, parian marble, astracane, pavonazzetto or Phrygian marble, Fior di Pesco or Chalcidicum, yellow breccia, African breccia, giallo antico or Numidian marble, rosso antico, portasanta, greco scrittp, grigio antico, cipollino imezio, cipollino from Karystos, black and white granite, sagario, breccia di Sette Bassi, grey morato, and broccatello from Spain.

Porphyry is a volcanic stone with a reddish purple shade. This color has always had a symbolic meaning and is historically linked to imperial power. In Classical and Byzantine times, purple porphyry discs (often derived from horizontally cut columns) were placed at strategic points along the paths of court ceremonies and in specific places connected to liturgy in Romanesque basilicas.

This magnificent floor’s original appearance remains a mystery, but, in the print Erasmo Gattola (a monk) made for his 1733 book Historia Abbatiae Cassinensis, there are several motifs that commonly appear in Classical and Byzantine examples. These reappear later in the rich repertoire of Roman Cosmatesque work.

The smaller decorative motifs are composed mainly of regular geometric shapes: squares, triangles, rhombi, hexagons and octagons. When combined together, they form more complex geometric patterns (like checkered patterns, squares inscribed in other squares, etc.).

At their root, the decorative patterns can be broken down into a geometric matrix that regularly guides the tiles’s layout.

The decorative motifs used in medieval marble pavements are almost always derived from the Classical tradition. New floors often foresaw the reuse of old materials, including the use of pre-cut tiles coming from older pavements. This process encouraged artists to reproduce traditional, ancient patterns.

In Montecassino’s medieval pavement, drawn in Gattola’s print, we can appreciate many marble discs (rotae in Latin) surrounded by other curvilinear patterns; they formed the so-called quincunx pattern which was widespread in Roman and Byzantine pavements. This word comes from the Latin for “five ounces”, an ancient unit of measurement. It indicates the pattern formed by five points arranged the same way as those on the corresponding face of a die.

FRAMMENTO CON MOTIVO A CROCI

This fragment, recovered after the last World War along with the others, is part of what survives from Desiderius’ pavement.

This decorative motif is seen at Montecassino and as well as in other pavements where craftsmen from Desiderius’ campaign worked: Sant’Angelo in Formis, San Benedetto in Capua, Santa Maria Maggiore in Sant’Elia Fiumerapido, and San Menna in Sant’Agata de’ Goti.

The decoration consists of a succession of alternating crosses in white palombino, giallo antico and alternating red and green porphyry.

Fragment with Checkered Patterns

This is the only surviving piece of the eastern portion of the nave, recovered after World War II. It formed part of a triangular motif that created an octagonal frame around an eight-pointed star.

It presents a simple checkerboard pattern made of red porphyry, green porphyry and white palombino tiles. There are also some pieces in giallo antica of Numidia.

The entire panel—where fleur-de-lis patterns were visible—could have been refurbished and added to in the 13th century.

The tiles alternate chromatically: almost all red ones are found on one side of the triangle and almost all green ones on the other.

Fragment with Checkered and Geometric Patterns

The fragments are surviving pieces from some of the panels from Desiderius’ pavement that were recovered after World War II along with other fragments.

The simplest pattern is the checkerboard where we see alternating tiles of green porphyry, giallo antico of Numidia and white palombino. Another pattern is composed of white marble and palombino octagons between which there are red and green porphyry squares. This is an ancient and traditional pattern, already seen in late Roman and Late Antique pavements (4th -5th centuries).

Other pieces are variations of the rhombus pattern and are quite widespread among the pavements made by craftsmen coming from Desiderius’ decorative campaign (Sant’Angelo in Formis, San Benedetto in Capua, Santa Maria Maggiore in Sant’Elia Fiumerapido, and in San Sant’Adriano Demetrius Crowns).

In some cases, the rhombi consist of a single marble tiles (in yellow breccia, giallo antico of Numidia, white marble), framed by plaited ribbons in white marble, red porphyry, green porphyry and giallo antico of Numidia. In others, the rhombi create a checkerboard pattern (with white marble with red porphyry, green porphyry, lumachella, and broccatello), framed by white marble ribbons of in red and green porphyry at their intersections.

Fragment with Herringbone Pattern

This fragment, recovered after the last World War, is part of what survives from Desiderius’ pavement.

This decorative pattern is an ancient one called opus spicatum, which in Latin means “work shaped like a blade of wheat” and can already seen in Classical, Roman floors.

This motif is widespread at Montecassino and as well as in other pavements where craftsmen from Desiderius’ campaign worked (Sant’Angelo in Formis, San Benedetto a Capua, Santa Maria Maggiore in Sant’Elia Fiumerapido, and Sant’Adriano in San Demetrio Corone).

As in other, contemporary examples, the distinctive trait of this pattern is the use of juxtaposition of different types and colors of marble.

Fragment with Discs and Checkered Pattern

These fragments are portions of panels coming from Desiderius’ pavement, recovered after the last World War.

The simplest design is made with porphyry discs. The spaces between the discs are composed of white palombino tiles forming four-pointed stars. The abundance of porphyry, a rare material in the Middle Ages, conveys the abbey’s wealth in the second half of the 11th century.

The other pattern would later be used by Cosmatesque craftsmen working in Rome between the 12th and 15th centuries. It consists of large, white square tiles framed by smaller, square and triangular tesserae, arranged in a checkerboard. The squares are made in light marbles like pavonazzetto and cipollino, while the triangles are made of red and green porphyry.

Fragment with Checkered, Geometric Patterns

The fragments are some of the surviving portions of certain panels of Desiderius’ pavement, recovered after World War II.

The designs are some of the most Classic and traditional ones, already seen in late antique Roman pavements (4th-5th centuries), based on the use of alternating triangles and squares to create checkerboard patterns with numerous variations of smaller squares rotated at a 45° angle within other squares or triangles inscribed inside other triangles. The most complex pattern consists of hexagonal tesserae in white palombino and triangular tesserae in red and green porphyry forming six-pointed stars.

Among the marbles used are: imperial red porphyry, green porphyry, giallo antico of Numidia, yellow breccia, pavonazzetto, greco scritto, cipollino, grigio antico, and palombino.

Fragment with Dogs (Greyhounds)

These two fragments are surviving portions of Desiderius’ pavement recovered after World War II.

They represent hunting dogs (greyhounds) and act as guardians of a holy place. We do not know the exact, original location of the two panels. They may have been located at each side of the abbey church’s altar to guard the remains of St. Benedict, which were located under the altar in a tomb in the church’s crypt which could be seen through a small window.

In his Chronicle, Leo Marsicanus, a monk at Montecassino at the time of Abbot Desiderius (1058-1087), refers to animated figures (animatas figuras) perhaps in reference to these two dogs.

By comparing these figures to an opus sectile lion in the church pavement of Sant’Adriano at San Demetrio Corone (Cosenza), we can exclude that the panel with the dogs were originally installed vertically. This comparison also allows us to verify the importance of Desiderius’ decorative campaign in disseminating this technique throughout the southern part of the Italian peninsula.

The tiles are made of natural materials (white palombino and rosso antico), except for some portions made with glass paste tesserae, possibly due to subsequent restoration.

[imagine del leone] San Demetrio Corone, church of Sant’Adriano, pavement in opus sectile, detail of the lion. Circa 1105.